Understanding the ingredients of commercial diversity

An equitable high-density urban environment offers commerce and services to all social groups, regardless of income, age or ethnicity. The Bugis district in downtown Singapore – one of the most diverse commercial quarters of the city state – offers spaces and amenities to all of the city-state’s inhabitants, ranging from small Buddhist paraphernalia stores, to countless eateries, boutiques, book stores, textile traders, electronics dealerships, community clubs, health care services, complete with class “A” office space, banks and modern shopping malls. The illustration above, which is also downloadable as a info-graphic on the side, presents an imaginary area that resembles Bugis and introduces nine policy and planning lessons that may be generalized from its structure for achieving diversity, accessibility and inclusiveness elsewhere.

1. Neighborhood Density and Socio-economic Diversity

Who visits stores, how often, and consequently what stores survive, depends on who lives in their catchment area and at what densities. Higher densities that accommodates a diverse set of class, race, ethnic, age and gender groups, can generate enough demand for infrequently bought goods like specialized furniture, or ethnic restaurants, while businesses selling frequently bought goods, such convenience stores, can survive even in low density homogeneous settings.

2. Zoning

Zoning guidelines can designate a particular type of business or function, such as food and beverage outlets, in desired locations. If combined with appropriate tax or rent support, zoning can help achieve amenities that the market alone might not produce.

3. Public transit Access

Accessibility not only depends on routes and destinations within walking range, but also on more distant metropolitan or regional location qualities. A well-connected transit system can deliver customers from all corners of a city. Access to a wider clientele provides a strong incentive for commerce to locate around transit stations. Different stores may be attracted to different transit lines.

4. Tenant Coordination

Asking reduced rent from desirable tenants that deliver needed services, that add to the character of a place or that attract desired clientele, is a strategy commonly used by mall owners, local governments, business associations and other landlords.

5. Municipal Spaces

Municipally owned commercial spaces (e.g. public housing blocks) tend to produce a different commercial image and rarely attract high-end chain stores. They are well suited to small individually owned enterprises.

6. Variable Horizontal Accessibility

Location and accessibility play a key role in the value of a storefront. Neighborhoods that offer different levels of accessibility and visibility on various streets are more likely to attract a range of diverse businesses with different exposure needs and financial abilities. Side streets and back alleys often house businesses that cannot afford rents on main streets. No matter how big the flow, stores prefer to face the street, as close as possible to passing foot-traffic.

7. Clustering

Regardless of location, clustering helps stores do better business. An agglomeration of stores attracts more customers by offering complementary goods or allowing customers to engage in price and merchandise comparison. Places that accommodate different stores in close proximity are more likely to serve diverse needs. Environments with small parcels and numerous buildings close to each other are enablers for retail clusters.

8. Variable Building Types

Different commercial activities require different spaces. Environments that offer a diverse building stock are more likely to attract variable commercial tenants.

9. Variable Vertical Accessibility

Location and accessibility also play out vertically - upper floors are commonly less valuable, unless they offer something extraordinary, such as views. In Singapore, public housing block podiums with commercial spaces up to the fourth floor offer elegant examples of vertical access differentiation. Out of the way and out of sight, upper floors are well suited for lower-revenue businesses, such as specialised services, non-government organisations, and educational facilities. These mixed-use public housing typologies enable such businesses to survive in otherwise priced-out areas.

10. Food Trucks / Hawkers

Commercial diversity can also be enhanced with smaller scale mobile solutions – food trucks, mobile carts, street hawkers, etc. Mobile vendors typically pay less rent than larger fixed tenants, making it possible for a greater range of sellers to operate.

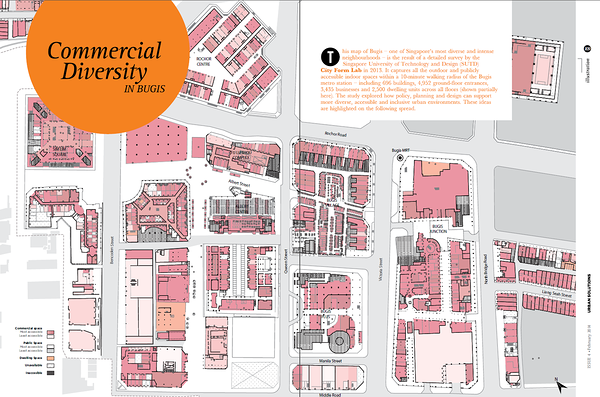

Bugis, Singapore

The following map of Bugis – one of Singapore’s most diverse and intense neighbourhoods – is the result of a detailed survey by the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) City Form Lab in 2013. It captures all the outdoor and publicly accessible indoor spaces within a ten-minute walking radius of the Bugis metro station – including 696 buildings, 4,952 ground-floor entrances, 3,435 businesses and 2,500 dwelling units across all floors (shown partially here). The study explored how policy, planning and design can support more diverse, accessible and inclusive urban environments. These ideas are highlighted on the following spread. (Download the map here for hi-res PDF).